| ����Task Force Report: Chapter 1 |

Introduction

The

Earth has been under a constant barrage of objects from space since its

formation four and a half billion years ago. They cover a wide range,

from the very small to the very big, with greatly different rates of arrival.

Every day hundreds of tonnes of dust enter the upper atmosphere; every

year objects of a few metres diameter do likewise, and some have effects

on the ground; every century or so there are bigger impacts; and over

long periods, stretching from hundreds of thousands to millions of years,

objects with a diameter of several kilometres hit the Earth with consequences

for life as a whole.

The

Earth has been under a constant barrage of objects from space since its

formation four and a half billion years ago. They cover a wide range,

from the very small to the very big, with greatly different rates of arrival.

Every day hundreds of tonnes of dust enter the upper atmosphere; every

year objects of a few metres diameter do likewise, and some have effects

on the ground; every century or so there are bigger impacts; and over

long periods, stretching from hundreds of thousands to millions of years,

objects with a diameter of several kilometres hit the Earth with consequences

for life as a whole.

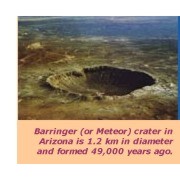

For long there was an unwillingness to recognise that the Earth was not a closed system on its own in space. The vast increase in knowledge over the last half century has shown otherwise. For example, it is now widely accepted that the impact in Yucatan caused the global changes associated with the end of the long dominance of the dinosaur family, some 65 million years ago. The huge Barringer crater in Arizona, created some 49,000 years ago, was attributed to volcanic action. Even the destruction of thousands of square kilometres of forest in Siberia in 1908 was somehow brushed aside. An equivalent impact on a city would eliminate it within a diameter of about 40 kilometres, say the diameter of London�s ring road, the M25. Although over two-thirds of the Earth is covered by water, and much of the remainder is desert, mountain or ice-cap, traces of many previous impacts can now be found.

This bombardment is integral to life on Earth.The Earth was formed of the same material.Without carbon and water there could be no life as we know it. Periodic impacts have revised the conditions of evolution, and shaped the course of the Earth�s history. As a species humans would not now exist without them. On one hand we can rejoice in them; on the other we can fear for our future.

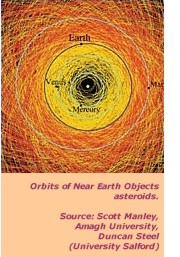

Understanding of the threat from Near Earth Objects � asteroids, long- and short-period comets � is relatively new (see Chronology at Annex A).With gathering evidence of past impacts, and a possible analogy with the effects of nuclear war, the general public as well as the astronomical and military communities began to take a somewhat anxious interest.The spectacle of the comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 colliding with the planet Jupiter in July 1994, throwing up fire-balls as big as the Earth, and such films as Armageddon and Deep Impact added to the concern.

Most practical work on the subject has so far been done in the United States.The US Congress and the US Administration through NASA and the Department of Defense have promoted studies and surveys, including the survey being done through a NASA programme at the Lincoln Laboratory of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Pioneering work has been done at the Minor Planet Center at Boston.

At international level there has been interest in the United Nations,

particularly at successive UN Conferences on the Exploration and Peaceful

Uses of Outer Space. The Council of Europe in Strasbourg, the European

Space Agency and many other bodies have drawn attention to the hazards.

The same goes for the International Astronomical Union, which brings together

astronomers from all over the world, and the Spaceguard Foundation set

up in Rome in 1996 with some national centres, including Britain.These

and other bodies organised an important conference in Turin in June 1999,

when a scale for measuring the effects of impacts was established. In Britain there has been interest in both Houses of Parliament,

and a debate took place in the House of Commons on 3 March 1999.This was

followed by the creation of the present Task Force by the Minister for

Science in January 2000.

established. In Britain there has been interest in both Houses of Parliament,

and a debate took place in the House of Commons on 3 March 1999.This was

followed by the creation of the present Task Force by the Minister for

Science in January 2000.

In the Report which follows, the Task Force examines the nature of the asteroids and comets which circulate within the Solar System.We look at the facilities required to identify the orbits and composition of those coming near the Earth which range, in the words of a distinguished American astronomer, �from fluff ball ex-comets to rubble piles, solid rocks and slabs of solid iron�, each with different consequences in the event of terrestrial impact.We look at the effects of such impacts, according to size and location.They include blast, firestorms, intense acid rain, damage to the ozone layer, injection of dust into the atmosphere, tsunamis or giant ocean waves, and possible vulcanism and earthquakes. We then assess the risks and hazards of future impacts.

Building on the work already done, we consider how a worldwide effort might be best organised and coordinated, and what the British contribution might be, both in national and international terms. Here an element of particular importance is public communication, which should be neither alarmist nor complacent. Finally we look into the fundamental problem of action in the event of an emergency. Should we do as has been done in the past, and simply let nature take its course? Should we plan for civil defence, trying, for example, to cope not only with direct hits but with such side effects as tsunamis? Should we help promote technologies which might destroy or deflect a Near Earth Object on track for the Earth? If so what methods should be used, and what would be the implications?

These and other issues are immensely difficult, and the Task Force does not have all the answers. But it is convinced that at a time when we understand better than ever before the consequences for the world as a whole, an international effort of research, coordination and anticipatory measures is required in which British science, technology and enterprise should play an important part.

Chapter 2 - Asteroids, Comets and Near Earth Objects

Annex A, Annex B, Annex C, Annex D, Annex E, Annex F

Crown Copyright � 2000. All rights reserved.

Conditions of Use